Steering the Dairy Ship in Uncharted Waters

Like the rest of the world, those who produce the dairy products that feed the world have been put through the ringer thanks to the global COVID pandemic.

At the annual meeting of National All-Jersey Inc. (NAJ) in late June, General Manager Erick Metzger explained the tremendous swings in dairy markets since March and offered suggestions on how dairy producers could protect margins in the future.

What Happened with Dairy Markets?

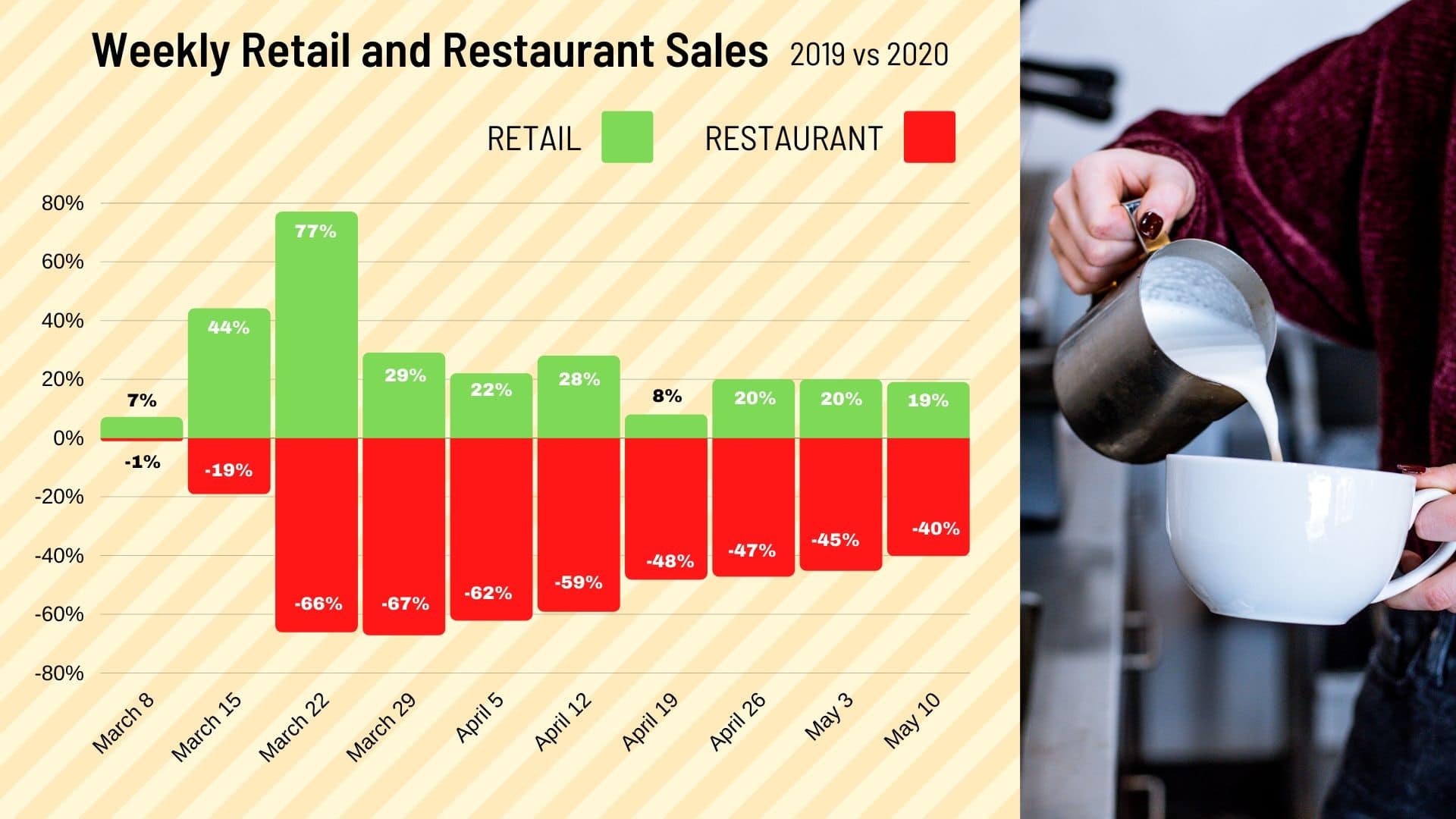

What has happened in dairy markets in the wake of the pandemic is unprecedented to say the least. In early March with the onset of stay-at-home orders and travel restrictions, there was a slight uptick of retail sales in grocery stores and a slight decrease in restaurant sales. Two weeks later, grocery stores were running out of product with a 77% spike in sales and restaurant sales were down 66% compared to last year. Grocery sales settled to about 20% higher than last year. Restaurant sales recovered slightly but continued to run more than 40% lower.

This wreaks havoc on infrastructure because manufacturers cannot pivot on a dime, moving product from food service to retail. There were a lot of dairy processors who were no longer taking in milk because they had more product than they needed and no buyers.

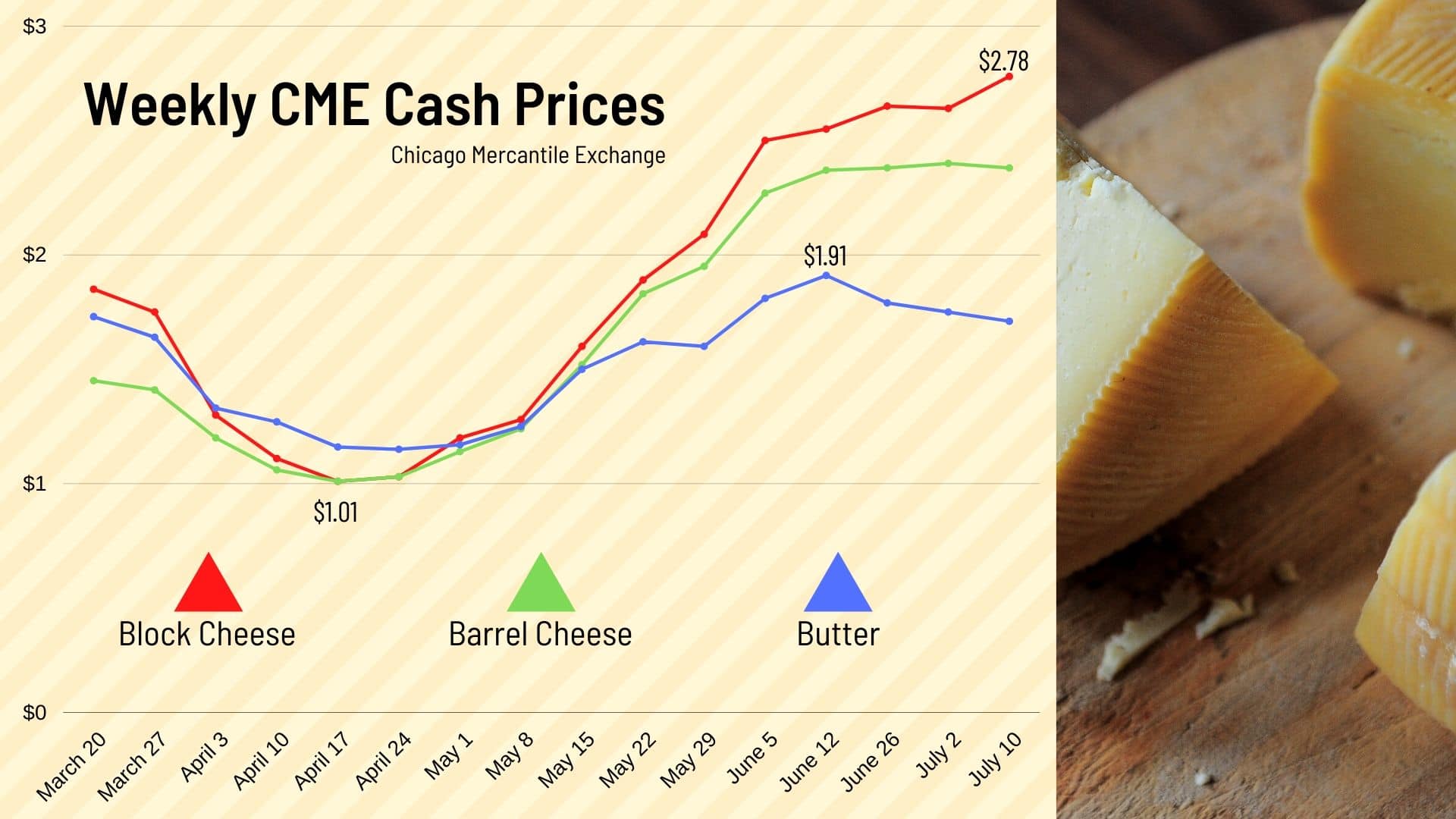

Prices on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) took a hit in late March and then plummeted in April, with block and barrel cheese trading for barely $1 a pound and butter at $1.15. And then, just as suddenly and unexpectedly, prices rebounded. The first week of May, all commodities saw a slight uptick to the $1.20 price range. Then they really took off, increasing about 20 cents a pound each week. By early June, block cheese was $2.50 a pound, butter was near $2.30 and barrel cheese was $1.75. Within a six-week period, block cheese moved from $1 a pound to a record $2.50 and was trading at $2.80 in late June.

What caused this? In a nutshell, supply decreased, and demand increased in significant ways. When prices fell to $1 a pound, many cooperatives established producer base excess plans tied to historical production. Anything under base was purchased at regular prices. Production above base was severely penalized, in some cases as much as $10-15 per hundredweight.

This strong incentive to cut production worked. While March production was 2.8% above last year and April was 1.4% ahead, May production fell 1.1% below last year. That 4% shift in production over three months is huge. What made it even more impactful was a 1.5% drop in production per cow as producers dried cows off early, switched from three times to twice daily milking and took energy out of the ration in favor of forages.

On the demand side, exports started to take off. When block and barrel cheese prices were $1 a pound, the U.S. was the world’s low-cost leader. A lot of export contracts began to be written. As well, government spending increased demand through programs including the Farmers to Families Food Box program and other USDA nutrition programs. In all, Uncle Sam is scheduled to purchase $1 billion in dairy products this year. The food service industry has rebounded as restaurants learn how to operate in a takeout and delivery world and replenish depleted inventories. Through it all, retail sales have continued to be strong as well.

What do dairy markets look like down the road? The biggest determining factor may be what happens on the supply side. How long will base excess plans stay in place, especially when Class III milk is now over $20 a hundredweight? How will production respond when cows that were dried off early begin to calve, producers return to three times daily milking and corn and other energy sources are added back into the ration? Non-milk check revenue plays a role, too. Programs including the Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) and Dairy Revenue Protection (DRP) are injecting cash into many farms and keeping them in business. This will also impact production.

On the demand side, just as low prices giveth, high prices taketh away. If high prices continue, the U.S. will become an import destination for cheese from other countries. Demand will also be determined by duration of government food assistance programs and the health of retail purchases as food service recovers and consumers begin to eat away from home again.

Dairy Insurance Program

Dairy producers can protect themselves financially by utilizing the insurance programs DMC and DRP. Both are subsidized by USDA and offer protection against severe price drops while maintaining opportunity to capitalize on high prices. They operate very differently, however.

DMC pays an indemnity when the national level for income-over-feed-costs falls below a level pre-selected by the producer. Premiums must be purchased for the entire calendar year and are fixed for the life of the current Farm Bill. Coverage is available for a dozen levels of margins, from $4 to $9.50, in two premium tiers based on a dairy’s historical production. Coverage for the first 5 million pounds of production at the $4.00 margin is free. Premiums for other coverage range from .25 cents per hundredweight to 15 cents per hundredweight for the first tier of production and from .25 cents to $1.813 per hundredweight (maximum margin $8) for the second tier of production.

DMC is available through USDA’s Farm Services Agency. Enrollment for 2021 runs from October 12 through December 11.

For dairy producers using DMC, NAJ recommends enrollment at the maximum $9.50 coverage (if eligible) for as long as possible. Projections for 2021 show margins dropping below $9.50 for just a few months, but the past three months are prime example of what can happen. DMC is an insurance program like any other, designed to protect against catastrophic loss. And don’t count on the free program providing any level of protection. Despite the worst industry conditions experienced in the past decade, margins never dropped below $4, so no indemnities were paid to producers at this level.

DRP insures against expected milk revenue rather than margin over feed cost and pays on a quarterly basis rather than monthly. Dairy producers can insure their entire production at the same premium rate. Coverage can be purchased any time in advance of the next quarter and up to five quarters in advance. Coverage for the last quarter of 2020 can be purchased through September. DRP is purchased through authorized crop insurance agents, with premiums based on Class III and Class IV futures contracts.

Other Topics

Metzger also discussed two other topics in his address to members: results from the A2 beta casein study co-funded by NAJ and the A2 Milk Company and negative Producer Price Differentials (PPDs). For additional information on the A2 study, read the June 2020 NAJ Equity Newsletter or watch a video on the AJCA YouTube Channel. Negative PPDs will be discussed in an upcoming post.